|

Paper is principally wood cellulose, which is considered a fibrous material. Cellulose is the second most abundant material on earth after rock. It is the main component of plant cell walls, and the basic building block for many textiles and for paper. Cellulose is a natural polymer, a long chain of linked sugar molecules made by the linking of smaller molecules. | |

|

| Cellulose hydrogen bonds. | |

|

The links in the cellulose chain are a type of sugar: ß-D-glucose. The cellulose chain bristles with polar -OH groups. These groups form many hydrogen bonds with OH groups on adjacent chains, bundling the chains together. The chains also pack regularly in places to form hard, stable crystalline regions that give the bundled chains even more stability and strength. This hydrogen bonding forms the basis of papercrete's strength. | |

|

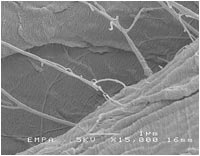

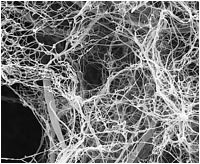

Viewed under a microscope, it's possible to see a network of cellulose fibers and smaller offshoots from the fibers called fibrils. |

| Fibrils are offshoots of fibers. |

|

|

|

When these networks or matrices of fibers and fibrils dry, they intertwine and cling together with the power of the hydrogen bond. |

| Fibers and fibrils network to form a matrix, which becomes coated with Portland cement. |

|

| |

Coating these fibers with Portland cement creates a cement matrix, which encases the fibers for extra strength. Of course paper has more in it than cellulose. Raw cellulose has a comparatively rough texture. Kaolinite or China clay is used to add smoothness and semi-gloss to paper. Varnish is added for the glossy look. Then there are various inks and other chemicals added. Many types of paper are treated with dyes and bleach that can contaminate soil and plant-life. They are extremely persistent in soil and cannot be broken down by bacteria. It makes sense to encase them in Portland cement, keep them out of the landfill, and do something useful with them.

|

| Samples made in a coffee can showing shrinkage. From left to right: No Portland cement, 50-50 cement to paper, 60-40 cement to paper. | Portland cement is an integral component of papercrete. It is usually not used in fidobe or padobe. A simple paper and water mix takes a great deal of time to dry and it shrinks about 15-25 percent. Adding Portland cement in an amount equal in weight to the paper cuts drying time by about half and reduces shrinkage to about 3-5 percent. If nothing were added to paper and water, it would be less strong, highly flammable, and less resistant to bugs and mold.

No matter what mix you settle on, the great thing about generic papercrete is how it traps air. When the water drains out and evaporates, it leaves thousands of tiny air pockets. This is what makes the material light and a good insulator. Adding solid material to the mix (sand, etc.) affects weight and insulating quality. The best mix is the one which best fits the application. | |

|

Because there is so much waste paper in the United States, it is probably the best fibrous material to use here. But there are many other natural fibrous materials, such as f lax, hemp and jute, which could be used to make papercrete in other parts of the world . Less obvious candidates include: straw, wood fiber, kenaf, wheat, barley and cane. Natural fibers have the advantage of being renewable. Also, many natural fibers, including pineapple leaf fiber and water hyacinth, are waste products and are available at minimal or no cost. Research is now being done to incorporate composites of these materials in ways previously unimagined. Ford Motors, for example, is committed to using wood and natural fiber-reinforced composites for structural purposes. Doing this would take these materials well beyond their present cosmetic uses in trim. Ford has even predicted that car bodies themselves will be constructed from natural fiber composites in the medium term.

This brings us back to some of the derivatives of papercrete - fibrous concrete, padobe and fidobe. Fibrous concrete (a.k.a. fibrous cement) is fibrous material (usually paper), Portland cement and water. Padobe (paper adobe) has no Portland cement. It is a mix of paper, water, and earth with clay. Fidobe (fibrous adobe) is like padobe, but may contain other fibrous materials. Actually, classic adobe was made with clay earth and straw - so is adobe actually fidobe? I would guess so. There are no hard and fast rules, but recommendations are on the horizon.

| |

|

Papercrete is mixed with Portland cement to obtain a very good R-value (2-3 per inch), an excellent sound absorption quality, to be flame/fungus retardant, and bug/rodent resistant. Since it is relatively light and more flexible than earth, rock or concrete, it is potentially an ideal material for earthquake-prone areas. It can be used in many ways -- as blocks, panels, poured in place, augured, pumped, sprayed, hurled, troweled on, used like igloo blocks to make a self-standing dome or applied over a framework to make a roof or dome. Papercrete is a very forgiving material, but like any other mixture, varying the mix, admixtures and curing procedures results in tradeoffs in its properties. For example, adding more sand or glass to the mix results in a denser, stronger, more flame retardant material, but adds weight and reduces R-value. Heavy mixes with added sand, glass, etc. increase mass and strength to a point, but reduce workability. In other words, a "light" mix with just Portland cement is easier to cut with a chain saw and drive rebar through than a mix with larger amounts of sand, clay, etc. Adding more than the minimum amount of Portland cement to the mix increases strength and resistance to abrasion, but also reduces flexibility somewhat, adds weight and may reduce R-value. So the trick is finding the best mix for the application. Making walls calls for a lighter mix than stucco. Roof panels will probably be a different mix than sub-floors.

| |

|

A tow mixer being pulled behind a pickup truck.

|

The most common mixer in use is Mike McCain's tow mixer. See

Mixers. It has a capacity of about 200 gallons (900 liters). The following is a starting formula for a 200-gallon batch of blocks. A 200-gallon batch will make 25-30 blocks in forms one foot (30 centimeters) wide x two feet (61 centimeters) long x five inches (13 centimeters) thick.. See

Forms.

A starting formula is just that, a place to begin experimenting. Some people prefer "lighter" formulas without sand. If you plan to cut out windows, doors or other openings in the walls after they are erected, you will want to avoid using sand. It will dull your chainsaw blades very quickly.

But a typical starting formula for a 200-gallon batch is 160 gallons (727 liters) of water, 60 pounds (27 kilograms) of paper, 1 bag or 94 pounds (43 kilograms) of Portland cement and 15 shovelfuls or 65 pounds (29 kilograms) of sand. The sand adds thermal mass, reduces flammability and shrinkage, and packs down the slurry for a denser, stronger block. See above for caveats regarding sand.

Half a bag of Portland cement will work too, but the slurry will dry more slowly and will shrink more. The blocks won't be as hard or flame retardant when dry. Some people use two bags of Portland cement in areas where strength is most important - for blocks at the bottom of walls, roof panels, and for floors. Clyde T. Curry's recent formula for one yard (about 200 gallons) of papercrete incorporates 25% reground Styrofoam. His formula calls for three sacks of Portland cement added to 75 pounds of hammer-milled cellulose insulation and 25% reground Styrofoam. This cuts the amount of Portland cement he normally uses by one full sack and significantly reduces shrinkage. He makes his interior plasters using six sacks of Portland cement per yard, which makes the plaster fire resistant and forms a flame/vapor barrier equivalent to half-inch drywall.

| |

|

If you are opposed to using Portland cement, you should try some experiments with paper and clay and with other binders (see Other Binders below). There are some interesting websites on the internet, which give some fascinating insights into "paperclay." What you need for fidobe (any fibrous material and earth with clay) or padobe (paper and earth with clay) is a fibrous material or paper, and earth with high clay content. The clay content of the earth should be at least 30 percent. With regular adobe, if the clay content is too high the adobe may crack when drying, but adding paper fiber to the adobe mix strengthens the drying block and gives it some flexibility, which helps prevent cracking. The earth (with clay) to paper ratio can be varied for different applications. Since earth is different in every location, do some baseline experiments with 4-to-1 ratio - earth to paper, by weight. This is a good place to start in order to find a mix for a strong, lightweight block.

If Portland cement in small amounts is acceptable to you, you might try ratios like 6:3:1 or 7:2:1 paper, earth, cement. Basically, the more clay in the earth, the more paper you can use, but the binder should not fall under ten percent.

In the above ratios, keep in mind that the paper should be pulped with water before the other ingredients are added.

Before mixing the above ingredients, screen the rocks and small stones out of the earth. Again, the earth should have 30 percent clay or better. If you are wondering how you determine the amount of clay in earth, there are two easy ways. First of all, make sure you are testing earth with no organic materials in it. Usually that is found below the roots of plants and grass a foot or two underground. If you want to test a large volume of earth for clay content, make sure you a get a few handfuls from different points in the sample area and mix them together before screening. If there is any clay present, and it is the slightest bit moist, (spray some water on it if necessary) it will stick and cake up on your shovel making the shovel quite heavy. Take a handful of this damp earth and squeeze it. If it stays intact in a lump, it has some clay in it. If it can be rolled out into a "worm" without breaking up, it has more clay in it. If the worm can be draped over the edge of your hand about three inches and stay intact, it has quite a bit of clay in it. | |

|

|

|

| If the earth stays in a lump after squeezing, it has clay. |

If a worm can be made, it has more clay. |

If the worm will hang, it has a lot of clay. | |

|

To determine a fairly exact percentage of clay, do a simple "shake test". Using a vertical-sided transparent jar or glass which will take about a quart of liquid, fill it about two thirds full of water and almost the rest of the way with earth. (Leave a little space for shaking.) Then shake vigorously for at least two minutes. Set it down and start watching the separation. Earth should have some percentage of sand, silt and clay in it. Each material is basically a little more coarse and heavier than the other. Sand and heavier particles with fall to the bottom almost immediately - within a few seconds to a minute. Silt will settle on top of the sand in a few minutes to several hours. Clay will settle on top of the silt within several hours to 24 hours. Best to wait 24 hours for an accurate reading. There will be a faint but discernable delineation between each layer of material present. Of course, if any of the three materials - sand, silt, or clay is not present, there will be no layer. The percentage of clay can be determined by measuring the layers, and figuring the percentages, based on 100% of the total height measured. If the clay is about thirty percent of the height of the earth, you can make blocks. If it's within a few percent, you may want to use a little Portland cement to make up the difference.

I have seen something which makes me believe that going totally without Portland cement could be a problem - termites on the surface of a papercrete block. I was visiting a building site in New Mexico. Several hundred double fist-sized pieces of papercrete had been tossed in a pile and over a period of weeks had settled into the damp worksite soil. I began turning over pieces looking for any kind of damage. For some time I found nothing at all. Pieces embedded in damp mud for a long time were perfectly clean and intact. Then I found one, which had a small piece of unmixed paper embedded in it, which had been in contact with the damp soil for some time. The paper was not coated with Portland cement. There were a number of termites around the unprotected paper. The paper and mud scraped off very easily and I carefully examined the rest of the surface of the piece. It was completely clean. I then tried to break the piece into smaller pieces to look inside. It wouldn't break up and the small pieces that did come off left completely clean surfaces - no dirt tunnels or other evidence of termites. I believe that the uncoated piece of paper was the only thing drawing the termites. I have heard that some people put a shovelful of Borax in their mixes to discourage bugs. I have examined other buildings, five to nine years old, which I'm sure were built without Borax and they showed no obvious signs of bug attack.

Please consider a safety note on formulas. Unless you add a significant percentage of non-flammable material to any mix, both papercrete and fidobe (or padobe ) will burn. Papercrete made with a 4-to-1 ratio of cement to paper, by weight, won't burn at all, but that may be too much cement. Papercrete made with a 1-to-1 ratio of cement to paper, by weight, will smolder like charcoal, but does not burn with an open flame. Smoldering with no flame could result in unlikely but dangerous scenarios.

One practitioner is particularly sensitive to the possibility of a roof collapse should wide areas of a papercrete wall smolder for hours without detection. Another practitioner tested this possibility and thinks that such an occurrence is highly unlikely. He bored a three-inch hole in a papercrete wall and emptied an entire can of lighter fluid inside. He managed to get the papercrete to begin to smolder, but it would not continue to smolder for long because of lack of oxygen. It was suggested that fireproof mortar (high percentage of Portland cement or other fireproof binder) be used between the blocks, and fireproof stucco be used on the outside of the home to "encase" the blocks in fireproof "containers". This would limit a smoldering fire to the destruction of only one block, if it should ever occur at all.

Fidobe or padobe made with 3 parts soil to one part paper, by weight, supposedly won't burn either. Again, that may be too much soil. The intention is to be safe, but not sacrifice the qualities (R-value, light weight, strength, etc.), which make papercrete and its variations attractive to use in the first place. More testing needs to be done on papercrete and fire.

| |

|

There are alternatives to Portland cement, which can be used as binders, either alone or in combination with Portland cement. They include fly ash, bottom ash, rice hull ash, Plaster of Paris and lime. There may be others. Fly ash is ash left over from burning coal, which in the past was allowed to fly out of the smokestacks of power plants into the atmosphere. It is now caught in giant air filters, bagged and sold. I examined several structures built with papercrete block using fly ash and Portland cement in a 35 percent to 65 percent ratio as a binder. They were five years old and in excellent condition. Using fly ash as 35 percent of the binder cuts the Portland cement cost nearly in half and helps recycle fly ash. Bottom ash is heavier than fly ash so it sinks to the bottom of the furnace. I have heard of bottom ash being used, but have not seen papercrete made with it. Rice hull ash is burned in power plants in areas of the country where rice is grown. We currently have 100 pounds (45 kilograms) of rice hull ash on standby for tests. Test results with rice hull ash will be posted in

Tests soon. Plaster of Paris is a variety of calcined gypsum. You probably have seen it in the form of drywall sheets. In powder form, it is really quite expensive, but in situations where it is necessary to join papercrete and wood, it is very effective. A small sample made with it was placed on a 2 x 6 piece of wood and was very difficult to pry off with a trowel. The papercrete seemed literally glued to the wood.

Hundreds, if not thousands of years before Portland cement was discovered, lime was used as a binder, mortar and plaster. The Romans used it in their stone construction. It can be purchased in most home improvement stores. More tests need to be done on all of these binders. We will be working on testing them later this year.

| |

|

It took me some time to get over my skepticism about papercrete. I mixed up small batches and tried different formulas. Since I have no allergies, and was used to thinking in terms of bricks and mortar, I just felt more confident using Portland cement. I found some recycled plastic five-gallon buckets to work in and bought an "X" shaped stucco-mixing blade for my heavy-duty drill to do the mixing.

|

X-shaped stucco mixing blade.

|

The drill won't win any RPM contests, but has great low-end power. I would advise staying away from the normal kitchen blender for doing experimentation. I burned out a blender and a circular saw (I had custom adapted it for mixing.) before I realized that those tools are really meant for high speed and relatively low torque. Recently, I was told that a heavy-duty food processor works well to mix papercrete samples. What you need to mix papercrete is power. You need to tear the paper apart and mix it, which requires a good deal of force. This is the reason that Mike McCain's tow mixers work well - they provide the power of an automobile engine to tear apart everything from office paper to phone directories.

|

| 1250 pounds on block made of paper and water only. | After carefully weighing the components with a three-bar scale and mixing small batches, I poured samples in open-ended coffee cans and placed them on shade cloth to drain. I usually waited about an hour to remove the coffee can. The samples dried in about four days in the hot and dry weather of the Phoenix area . I recommend that anyone considering papercrete do a little experimentation to build confidence in the material. My confidence soared when I let down a front tire of my truck - over 1200 pounds (545 kilograms) on a bread-loaf size piece of papercrete made with just paper and water. It didn't leave a mark on the papercrete. Supposedly, computerized algorithms could tell me what would happen if I left the truck there for 200 years. | |

|

|

| | | |